Fermentation in the Family

My entire life I have been in awe of the story of my maternal grandmother. She apparently was renowned for her beauty in Jeolla province, which is lovely. More importantly, she was a phenomenal cook. And even better, she ran her own winery making makgeolli or Korean rice wine like a boss. Makgeolli is a wine produced from rice that has been fermented with yeast, is cloudy-white from rice sediment and sometimes slightly fizzy. It was historically looked down at as a farmer’s drink and remains much less expensive than other alcohols. However, in the past five years or so, makgeolli has had a resurgence as a new generation has focused on craft liquors and traditional Korean methods of fermentation.

My grandmother had her makgeolli winery in an era when Korean women were not supposed to work, especially if they did not have to. In the time I knew her, she was like a fairy godmother who always met my brother and I laden with gifts, so much so that our nickname for her was Santa. She was sadly bedridden for most of my childhood but always elegant and discreet. So I was fascinated that in her previous life she made makgeolli by the barrelfuls in the countryside. In my romantic childish fantasies, she was the most beautiful bootlegger of the South.

Alas, in a common rural narrative, my mother and her siblings didn’t want to carry on the makgeolli business, and instead had aspirations for the city. The winery was sold years before I was born. For a while, I've wanted to locate my grandmother’s winery, revive and rebrand it and distribute a new makgeolli inspired by her. I’ve been pestering my family about the location and details about the winery, but sadly everyone's memories have faded.

Last week, I met a young man who is basically living my makgeolli dream. Minkyu Kim, if you and your family weren’t so kind, I would be cursing your name in jealousy.

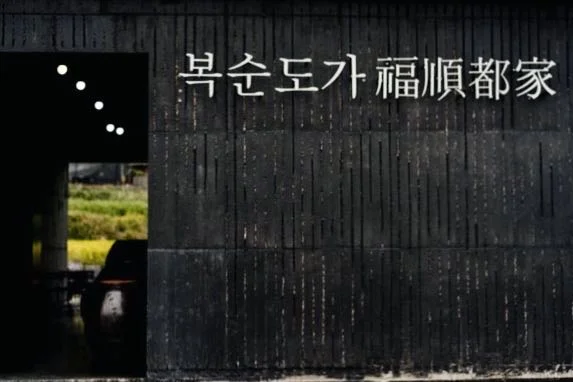

Minkyu’s mother and her family have been making makgeolli for home use in a small town near Busan for generations. Minkyu trained as an architect in Korea and in the U.S., and bounces back and forth from Seoul to Busan to the town of Ulsan where his family’s winery is located. While he was still an architecture student at Cooper Union in New York, Minkyu and his younger brother helped his parents create a real business out of his family’s hobby. Minkyu sees fermentation and the craft of making makgeolli as a true art form, and his approach to the family business is almost more philosophical than commercial. His thoughtfulness is seen in so many decisions around the new company which is known as Boksoon Doga. Informed by Minkyu's architectural background and international life, Boksoon Doga has become one of the most respected and elevated makgeolli businesses today.

Boksoon is Minkyu's mother’s name, which I especially find beautiful since I named my business, Sook, after my own mother. It is Boksoon Park’s recipe, handed down from her family, that is the base of the business, and so of course the company should be named after her. Doga is the Korean term for a liquor-making family, made up of two Chinese characters - one for do and one for ga, which means family. In Korean, many names are underpinned by Chinese characters with their own individual meanings. The Chinese character usually used for do in this word implies a special designation for a family that makes liquor. Since Minkyu’s family were never professional liquor producers, they cannot use the traditional Chinese character for do. Instead, Minkyu chose the Chinese character for city, which is also pronounced do. This change in the Chinese spelling is an act of respect but also a conscious linking of their rural tradition to the modern city.

I was lucky enough to visit the winery during the time that Minkyu says is the most beautiful time of year – harvest time. Surrounding the winery are the rice paddies where all the rice for the brewing comes from. The fields are mostly golden, no longer green, and yielding the grains to be fermented. Newly harvested rice is scattered on mats on the roads around the winery so it can dry. Local residents continue to farm the land. And during their breaks, there is laughter and stories over fruit plucked from neighbouring trees - and of course there is makgeolli.

In the open kitchen of the winery, Minkyu’s mother usually prepares meals for her family and for the staff. Our feast included haemul buchujeon or seafood chive pancakes to start, and then platters of bossam or steamed pork belly with fresh kimchi made with chillies, nuts and raisins in her own style. Minkyu’s mother makes most of her ingredients by hand, from her fish sauces to the soybean paste with which she made soup that day. Her son has plans to sell her pastes and fish sauce in a later phase of the business, but for the moment all the pastes she makes she gives to members of her church. “That’s a lot to give away,” Minkyu said half-joking when he saw the tall stacks of crates of jarred pastes intended for the church. Luckily, his mother saved me a jar each of her chilli paste and soybean paste, which are complexly rich with umami and completely natural.

I loved watching Minkyu’s mother cook. She has an ease about her, handed down to her from her mother no doubt. Seeing her use her hands to dress the cabbage to make kimchi, I could tell before I tasted her food that she had hands that made delicious food. There’s a Korean expression sohn maht, which literally means the taste of one’s hands, but is used to express the gift that certain hands have for making food taste good. Minkyu’s mom has amazing sohn maht. Now I've tried her food and can vouch for it.

The building where Minkyu’s mother cooks also houses the brewing operations and was designed by Minkyu. The structure reflects his own theory of what he calls fermentation architecture. For Minkyu, the winery is more than just a place to make alcohol, it embodies the change and interaction that is inherent in fermentation. Fermentation is itself a process where various ingredients such as rice and yeast interact with each other and transform and create new substances such as alcohol and gas. The winery is a single-story rectangular building, blackened by carbon from burnt rice straw and reinforced by exposed rope, which is intended to decompose over time. When you enter the main hallway, a soft soundtrack plays which turns out to be the crackling and hissing sound of fermenting rice. When you bend your ear over one of the earthenware jars of fermenting makgeolli, you are overwhelmed by the sweet smell of yeast and can hear the same crackling noise.

Minkyu chose the colour black for the building because before it was built, the area had a tragic wildfire which marred the countryside. During that time, Minkyu was touched by how the town’s residents united to help each other, and so he used the image of the blackened landscape in his architecture to reframe it as a symbol of community. Now the winery already attracts visitors, and there are plans for a café onsite. They are also building restaurants in Busan with other local producers to highlight their makgeolli.

I wish I could have stayed a bit longer at the winery. It’s close to Ulsan’s KTX station where a speed train would take me back to Seoul. Before we entered the train station, Minkyu pointed out where there were ongoing disputes over land development and in the meantime, the land near the station lays fallow and wasted. “People in Seoul think about things like design, but they have no idea what’s going on in the countryside. I hope we can change that.”

Boksoon Doga

Hyangsandong-gil 48, Sangbuk-myeon, Ulju-gun, Ulsan

http://boksoondoga.com